Sefer Tepe’s Stone Faces: Expanding Symbolism of Karahan Tepe

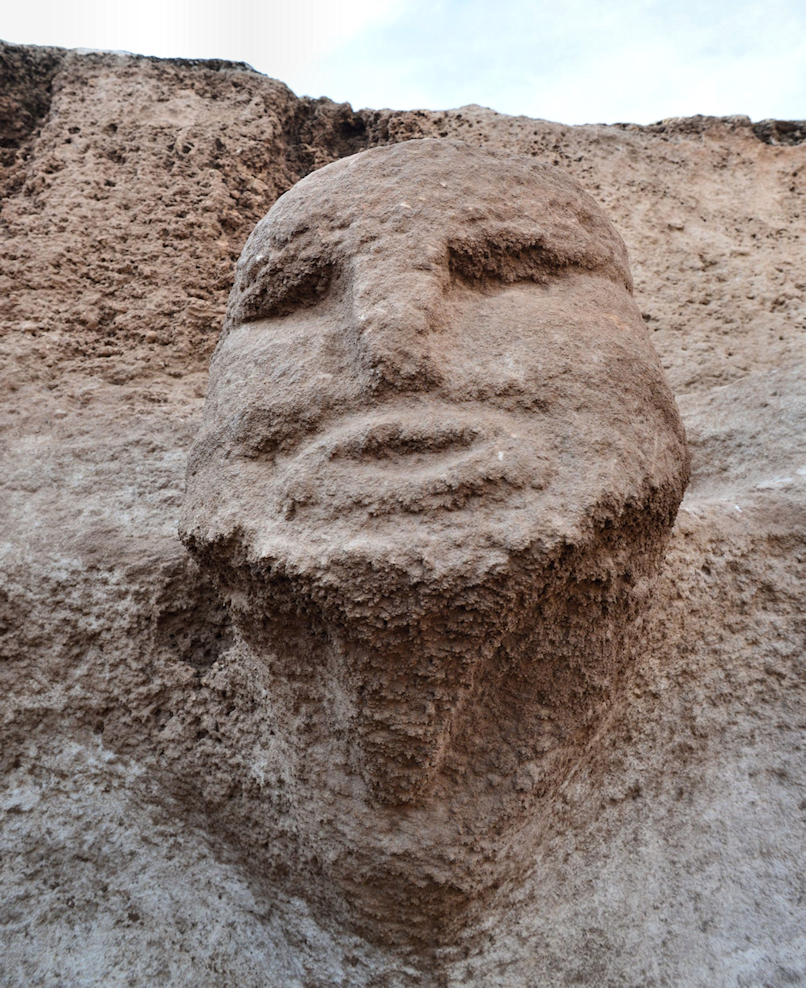

Stone head attached to slab at Sefer Tepe (Sefertepe Excavation Team)

The Power of the Head: Sefer Tepe, Karahan Tepe, and a Shared Neolithic Obsession

The recent discovery of a stone slab with two carved human heads at Sefer Tepe adds a significant piece to the growing puzzle of Taş Tepeler symbolism.

While striking on its own, the double-headed motif does not stand in isolation. Similar emphases on the head, including isolated faces, decapitated imagery, and mirrored forms, appear at Karahan Tepe and across the broader Upper Mesopotamian region.

This raises an important question: what did the head represent within these early Neolithic communities, and why was it repeated with such persistence?

Double head stone slab at Sefer Tepe (@ Stone Mounds)

The Sefer Tepe Heads in Context

The Sefer Tepe piece is a carved architectural slab, most likely integrated into a wall or structural feature. Two human heads emerge from either end of the stone, creating a clear symmetry.

The heads sit at the limits of the slab, almost defining its edges. They are not decorative additions placed in empty space. They structure the boundaries of the slab itself.

At Göbekli Tepe, the human presence is often abstracted through T-shaped pillars and stylized reliefs. At Karahan Tepe, isolated heads and anthropomorphic carvings emphasize the upper body and face. Sefer Tepe continues that pattern by isolating the head as the primary expressive element within architecture.

Across the Taş Tepeler region, the head is repeatedly separated from the body, carved independently, or embedded in built space. The Sefer Tepe slab fits obviously and clearly into that larger pattern.

This consistency suggests importance.

The Karahan Tepe head

At Karahan Tepe, the emphasis on the head is direct and intentional.

Excavations have revealed carved human faces emerging from the bedrock within circular structures. These are not loose objects. They are integrated into the architecture itself. The face looks outward from the wall, positioned where it would have been visible to anyone inside the enclosure.

Karahan Tepe has also produced ribbed anthropomorphic figures, where the torso is skeletal in appearance.

Gobekli Tepe shows also examples of decapitated imagery and isolated heads. Bodies appear without heads. Heads appear detached from bodies. The fragmentation does not seem accidental. This, along with the ritualistic placement of skulls and bones - points to a death cult or emphasis on death as a cultural expression.

Karahan Tepe ribbed-man statue

Why the Skull and Head?

Across the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of Upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, skulls were not left in the ground undisturbed.

They were removed from burials, curated, and in many cases, they were plastered and modified. They were then placed beneath floors or within architectural niches. This is a repetitive deliberate post-burial ritual activity. The skull appears to have been treated differently from the rest of the body.

In settled communities emerging for the first time in human history, ancestry suddenly mattered in new ways. When people stop moving seasonally and begin anchoring themselves to place, lineage becomes territorial.

Skulls may have functioned as tangible anchors to that lineage.

By keeping the head, communities may have maintained continuity between the living and the dead. The dead were not absent. They were integrated into domestic or communal space.

When we return to Karahan Tepe and the double-headed slab at Sefer Tepe, the carved stone heads begin to look less like decoration and more like architectural echoes of this same logic.

Double headed figure found at Karahan Tepe (@ Dakota Wint taken at Sanliurfa Museum)

The Meaning of the Double Head

Doubling in early symbolic systems often encodes duality. It can represent life and death, male and female, ancestor and descendant, interior and exterior, human and other. In societies where cosmology is embedded in architecture rather than written in text, such relationships are often expressed visually.

At Karahan Tepe, pairing appears in other forms, including a double headed character and mirrored fox relief.

Mirrored Foxes found on T-pillar at Karahan Tepe

At Çayönü, another early Neolithic settlement in southeastern Anatolia, a carved double-headed human figure has been documented within a ritual architectural context. Çayönü dates to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period and is well known for its evidence of structured communal buildings, skull removal practices, and early experiments in settled life.

Double headed figure from Cayonu

The presence of a double-headed figure there is significant because Çayönü sits within the same broader Upper Mesopotamian cultural sphere as Karahan Tepe and Sefer Tepe. It shares architectural innovation, ritual treatment of the dead, and symbolic emphasis on the human form.

Double headed figure from Ain Ghazal in Jordan

Another important example comes from Ain Ghazal in Jordan, where a monumental two-headed plaster statue dating to around 6500 BC was found. While separated by geography and time from Taş Tepeler, the recurrence of a paired human form strengthens the case that dual imagery carried enduring significance within Neolithic societies of the region.

The double-headed slab from Sefer Tepe adds another piece to the story emerging across the region. The head clearly held meaning for these communities, and the repetition of the motif across multiple sites suggests it was not incidental.

We do not yet know exactly what the double head represented. But each new discovery brings more context. The journey continues :)

FREE KARAHAN TEPE E-BOOK

Sign up to our newsletter for a free Karahan Tepe E-Book